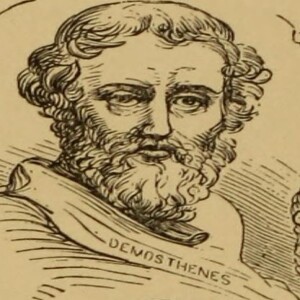

Had the question for debate been any thing new, Athenians, I should have waited till most of the usual speakers had been heard; if any of their counsels had been to my liking, I had remained silent, else proceeded to impart my own. But as the subjects of discussion is one upon which they have spoken oft before, I imagine, though I rise the first, I am entitled to indulgence. For if these men had advised properly in time past, there would be no necessity for deliberating now.

First I say, you must not despond, Athenians, under your present circumstances, wretched as they are; for that which is worst in them as regards the past, is best for the future. What do I mean? That our affairs are amiss, men of Athens, because you do nothing which is needful; if, notwithstanding you performed your duties, it were the same, there would be no hope of amendment.

Consider next, what you know by report, and men of experience remember; how vast a power the Lacedaemonians had not long ago, yet how nobly and becomingly you consulted the dignity of Athens, and undertook the war against them for the rights of Greece. Why do I mention this? To show and convince you, Athenians, that nothing, if you take precaution, is to be feared, nothing, if you are negligent, goes as you desire. Take for examples the strength of the Lacedaemonians then, which you overcame by attention to your duties, and the insolence of this man now, by which through neglect of our interests we are confounded. But if any among you, Athenians, deem Philip hard to be conquered, looking at the magnitude of his existing power, and the loss by us of all our strongholds, they reason rightly, but should reflect, that once we held Pydna and Potidaea and Methone and all the region round about as our own, and many of the nations now leagued with him were independent and free, and preferred our friendship to his. Had Philip then taken it into his head, that it was difficult to contend with Athens, when she had so many fortresses to infest his country, and he was destitute of allies, nothing that he has accomplished would he have undertaken, and never would he have acquired so large a dominion. But he saw well, Athenians, that all these places are the open prizes of war, that the possessions of the absent naturally belong to the present, those of the remiss to them that will venture and toil. Acting on such principle, he has won every thing and keeps it, either by way of conquest, or by friendly attachment and alliance; for all men will side with and respect those, whom they see prepared and willing to make proper exertion. If you, Athenians, will adopt this principle now, though you did not before, and every man, where he can and ought to give his service to the, state, be ready to give it without excuse, the wealthy to contribute, the able-bodied to enlist; in a word, plainly, if you will become your own masters, and cease each expecting to do nothing himself, while his neighbor does every thing for him, you shall then with heaven's permission recover your own, and get back what has been frittered away, and chastise Philip. Do not imagine, that his empire is everlastingly secured to him as a god. There are who hate and fear and envy him, Athenians, even among those that seem most friendly; and all feelings that are in other men belong, we may assume, to his confederates. But now they are all cowed, having no refuge through your tardiness and indolence, which I say you must abandon forthwith. For you see, Athenians, the case, to what pitch of arrogance the man has advanced, who leaves you not even the choice of action or inaction, but threatens and uses (they say) outrageous language, and, unable to rest in possession of his conquests, continually widens their circle, and, while we dally and delay, throws his net all around us. When then, Athenians, when will you act as becomes you? In what event? In that of necessity, I suppose. And how should we regard the events happening now? Methinks, to freemen the strongest necessity is the disgrace of their condition. Or tell me, do you like walking about and asking one another:—is there any news? Why, could there be greater news than a man of Macedonia subduing Athenians, and directing the affairs of Greece? Is Philip dead? No, but he is sick. And what matters it to you? Should any thing befall this man, you will soon create another Philip, if you attend to business thus. For even he has been exalted not so much by his own strength, as by our negligence. And again; should any thing happen to him; should fortune, which still takes better care of us than we of ourselves, be good enough to accomplish this; observe that, being on the spot, you would step in while things were in confusion, and manage them as you pleased; but as you now are, though occasion offered Amphipolis, you would not be in a position to accept it, with neither forces nor counsels at hand.

However, as to the importance of a general zeal in the discharge of duty, believing you are convinced and satisfied, I say no more.

As to the kind of force which I think may extricate you from your difficulties, the amount, the supplies of money, the best and speediest method (in my judgment) of providing all the necessaries, I shall endeavor to inform you forthwith, making only one request, men of Athens. When, you have heard all, determine; prejudge not before. And let none think I delay our operations, because I recommend an entirely new force. Not those that cry, quickly! to-day! speak most to the purpose; (for what has already happened we shall not be able to prevent by our present armament;) but he that shows what and how great and whence procured must be the force capable of enduring, till either we have advisedly terminated the war, or overcome our enemies: for so shall we escape annoyance in future. This I think I am able to show, without offense to any other man who has a plan to offer. My promise indeed is large; it shall be tested by the performance; and you shall be my judges.

First, then, Athenians, I say we must provide fifty warships, and hold ourselves prepared, in case of emergency, to embark and sail. I require also an equipment of transports for half the cavalry and sufficient boats. This we must have ready against his sudden, marches from his own country to Thermopylae, the Chersonese, Olynthus, and any where he likes. For he should entertain the belief, that possibly you may rouse from this over-carelessness, and start off, as you did to Euboea, and formerly (they say) to Haliartus, and very lately to Thermopylae. And although you should not pursue just the course I would advise, it is no slight matter, that Philip, knowing you to be in readiness—know it he will for certain; there are too many among our own people who report every thing to him—may either keep quiet from apprehension, or, not heeding your arrangements, be taken off his guard, there being nothing to prevent your sailing, if he give you a chance, to attack his territories. Such an armament, I say, ought instantly to be agreed upon and provided. But besides, men of Athens, you should keep in hand some force, that will incessantly make war and annoy him: none of your ten or twenty thousand mercenaries, not your forces on paper, but one that shall belong to the state, and, whether you appoint one or more generals, or this or that man or any other, shall obey and follow him. Subsistence too I require for it. What the force shall be, how large, from what source maintained, how rendered efficient, I will show you, stating every particular. Mercenaries I recommend—and beware of doing what has often been injurious—thinking all measures below the occasion, adopting the strongest in your decrees, you fail to accomplish the least—rather, I say, perform and procure a little, add to it afterward, if it prove insufficient. I advise then two thousand soldiers in all, five hundred to be Athenians, of whatever age you think right, serving a limited time, not long, but such time as you think right, so as to relieve one another; the rest should be mercenaries. And with them two hundred horse, fifty at least Athenians, like the foot, on the same terms of service; and transports for them. Well; what besides? Ten swift galleys: for, as Philip has a navy, we must have swift galleys also, to convoy our power. How shall subsistence for these troops be provided? I will state and explain; but first let me tell you why I consider a force of this amount sufficient, and why I wish the men to be citizens.

Of that amount, Athenians, because it is impossible for us now to raise an army capable of meeting him in the field: we must plunder and adopt such kind of warfare at first: our force, therefore, must not be over-large, (for there is not pay or subsistence,) nor altogether mean. Citizens I wish to attend and go on board, because I hear that formerly the state maintained mercenary troops at Corinth, commanded by Polystratus and Iphicrates and Chabrias and some others, and that you served with them yourselves; and I am told, that these mercenaries fighting by your side and you by theirs defeated the Lacedaemonians. But ever since your hirelings have served by themselves, they have been vanquishing your friends and allies, while your enemies have become unduly great. Just glancing at the war of our state, they go off to Artabazus or any where rather, and the general follows, naturally; for it is impossible to command without giving pay. What therefore ask I? To remove the excuses both of general and soldiers, by supplying pay, and attaching native soldiers, as inspectors of the general's conduct. The way we manage things now is a mockery. For if you were asked: Are you at peace, Athenians? No, indeed, you would say; we are at war with Philip. Did you not choose from yourselves ten captains and generals, and also captains and two generals of horse? How are they employed? Except one man, whom you commission on service abroad, the rest conduct your processions with the sacrificers. Like puppet-makers, you elect your infantry and cavalry officers for the market-place, not for war. Consider, Athenians, should there not be native captains, a native general of horse, your own commanders, that the force might really be the state's? Or should your general of horse sail to Lemnos, while Menelaus commands the cavalry fighting for your possessions? I speak not as objecting to the man, but he ought to be elected by you, whoever the person be.

Perhaps you admit the justice of these statements, but wish principally to hear about the supplies, what they must be and whence procured. I will satisfy you. Supplies, then, for maintenance, mere rations for these troops, come to ninety talents and a little more: for ten swift galleys forty talents, twenty minas a month to every ship; for two thousand soldiers forty more, that each soldier may receive for rations ten drachms a month; and for two hundred horsemen, each receiving thirty drachms a month, twelve talents. Should any one think rations for the men a small provision, he judges erroneously. Furnish that, and I am sure the army itself will, without injuring any Greek or ally, procure every thing else from the war, so as to make out their full pay. I am ready to join the fleet as a volunteer, and submit to any thing, if this be not so. Now for the ways and means of the supply, which I demand from you.

[Statement of ways and means.]

This, Athenians, is what we have been able to devise. When you vote upon the resolutions, pass what you approve, that you may oppose Philip, not only by decrees and letters, but by action also.

I think it will assist your deliberations about the war and the whole arrangements, to regard the position, Athenians, of the hostile country, and consider, that Philip by the winds and seasons of the year gets the start in most of his operations, watching for the trade-winds or the winter to commence them, when we are unable (he thinks) to reach the spot. On this account, we must carry on the war not with hasty levies, (or we shall be too late for every thing,) but with a permanent force and power. You may use as winter quarters for your troops Lemnos, and Thasus, and Sciathus, and the islands in that neighborhood, which have harbors and corn and all necessaries for an army. In the season of the year, when it is easy to put ashore and there is no danger from the winds, they will easily take their station off the coast itself and at the entrances of the sea-ports.

How and when to employ the troops, the commander appointed by you will determine as occasion requires. What you must find, is stated in my bill. If, men of Athens, you will furnish the supplies which I mention, and then, after completing your preparations of soldiers, ships, cavalry, will oblige the entire force by law to remain in the service, and, while you become your own paymasters and commissaries, demand from your general an account of his conduct, you will cease to be always discussing the same questions without forwarding them in the least, and besides, Athenians, not only will you cut off his greatest revenue—What is this? He maintains war against you through the resources of your allies, by his piracies on their navigation—But what next? You will be out of the reach of injury yourselves: he will not do as in time past, when falling upon Lemnos and Imbrus he carried off your citizens captive, seizing the vessels at Geraestus he levied an incalculable sum, and lastly, made a descent at Marathon and carried off the sacred galley from our coast, and you could neither prevent these things nor send succors by the appointed time. But how is it, think you, Athenians, that the Panathenaic and Dionysian festivals take place always at the appointed time, whether expert or unqualified persons be chosen to conduct either of them, whereon you expend larger sums than upon any armament, and which are more numerously attended and magnificent than almost any thing in the world; while all your armaments are after the time, as that to Methone, to Pagasae, to Potidaea? Because in the former case every thing is ordered by law, and each of you knows long before-hand, who is the choir-master. This was one of his tribe, who the gymnastic master, when, from whom, and what he is to receive, and what to do. Nothing there is left unascertained or undefined: whereas in the business of war and its preparations all is irregular, unsettled, indefinite. Therefore, no sooner have we heard any thing, than we appoint ship-captains, dispute with them on the exchanges, and consider about ways and means; then it is resolved that resident aliens and householders shall embark, then to put yourselves on board instead: but during these days the objects of our expedition are lost; for the time of action we waste in preparation, and favorable moments wait not our evasions and delays. The forces that we imagine we possess in the mean time, are found, when the crisis comes, utterly insufficient. And Philip has arrived at such a pitch of arrogance, as to send the following letter to the Euboeans:

[The letter is read.]

Of that which has been read, Athenians, most is true, unhappily true; perhaps not agreeable to hear. And if what one passes over in speaking, to avoid offense, one could pass over in reality, it is right to humor the audience; but if graciousness of speech, where it is out of place, does harm in action, shameful is it, Athenians, to delude ourselves, and by putting off every thing unpleasant to miss the time for all operations, and be unable even to understand, that skillful makers of war should not follow circumstances, but be in advance of them; that just as a general may be expected to lead his armies, so are men of prudent counsel to guide circumstances, in order that their resolutions may be accomplished, not their motions determined by the event. Yet you, Athenians, with larger means than any people—ships, infantry, cavalry, and revenue—have never up to this day made proper use of any of them; and your war with Philip differs in no respect from the boxing of barbarians. For among them the party struck feels always for the blow; strike him somewhere else, there go his hands again; ward or look in the face he can not nor will. So you, if you hear of Philip in the Chersonese, vote to send relief there if at Thermopylae, the same; if any where else, you run after his heels up and down, and are commanded by him; no plan have you devised for the war, no circumstance do you see beforehand, only when you learn that something is done, or about to be done. Formerly perhaps this was allowable: now it is come to a crisis, to be tolerable no longer.

And it seems, men of Athens, as if some god, ashamed for us at our proceedings, has put this activity into Philip. For had he been willing to remain quiet in possession of his conquests and prizes, and attempted nothing further, some of you, I think, would be satisfied with a state of things, which brands our nation with the shame of cowardice and the foulest disgrace. But by continually encroaching and grasping after more, he may possibly rouse you, if you have not altogether despaired. I marvel, indeed, that none of you, Athenians, notices with concern and anger, that the beginning of this war was to chastise Philip, the end is to protect ourselves against his attacks. One thing is clear: he will not stop, unless some one oppose him. And shall we wait for this? And if you dispatch empty galleys and hopes from this or that person, think you all is well? Shall we not embark? Shall we not sail with at least a part of our national forces, now though not before? Shall we not make a descent upon his coast? Where, then, shall we land? some one asks. The war itself, men of Athens, will discover the rotten parts of his empire, if we make a trial; but if we sit at home, hearing the orators accuse and malign one another, no good can ever be achieved. Methinks, where a portion of our citizens, though not all, are commissioned with the rest, Heaven blesses, and Fortune aids the struggle: but where you send out a general and an empty decree and hopes from the hustings, nothing that you desire is done; your enemies scoff, and your allies die for fear of such an armament. For it is impossible—ay, impossible, for one man to execute all your wishes: to promise, and assert, and accuse this or that person, is possible; but so your affairs are ruined. The general commands wretched unpaid hirelings; here are persons easily found, who tell you lies of his conduct; you vote at random from what you hear: what then can be expected?

How is this to cease, Athenians? When you make the same persons soldiers, and witnesses of the generals conduct, and judges when they return home at his audit; so that you may not only hear of your own affairs, but be present to see them. So disgraceful is our condition now, that every general is twice or thrice tried before you for his life, though none dares even once to hazard his life against the enemy: they prefer the death of kidnappers and thieves to that which becomes them; for it is a malefactor's part to die by sentence of the law, a general's to die in battle. Among ourselves, some go about and say that Philip is concerting with the Lacedaemonians the destruction of Thebes and the dissolution of republics; some, that he has sent envoys to the king; others, that he is fortifying cities in Illyria: so we wander about, each inventing stories. For my part, Athenians, by the gods I believe, that Philip is intoxicated with the magnitude of his exploits, and has many such dreams in his imagination, seeing the absence of opponents, and elated by success; but most certainly he has no such plan of action, as to let the silliest people among us know what his intentions are; for the silliest are these newsmongers. Let us dismiss such talk, and remember only that Philip is an enemy, who robs us of our own and has long insulted us; that wherever we have expected aid from any quarter, it has been found hostile, and that the future depends on ourselves, and unless we are willing to fight him there, we shall perhaps be compelled to fight here. This let us remember, and then we shall have determined wisely, and have done with idle conjectures. You need not pry into the future, but assure yourselves it will be disastrous, unless you attend to your duty, and are willing to act as becomes you.

As for me, never before have I courted favor, by speaking what I am not convinced is for your good, and now I have spoken my whole mind frankly and unreservedly. I could have wished, knowing the advantage of good counsel to you, I were equally certain of its advantage to the counselor: so should I have spoken with more satisfaction. Now, with an uncertainty of the consequence to myself, but with a conviction that you will benefit by adopting it, I proffer my advice. I trust only, that what is most for the common benefit will prevail.